Filichia Features: Happy 20th Anniversary to Rent

Filichia Features: Happy 20th Anniversary to Rent

Can it really be twenty years ago this week that Rent began rehearsals at the New York Theatre Workshop?

Little did anyone know at the time that Jonathan Larson’s musical would become an off-Broadway sensation. That was just the start: Broadway beckoned, so Rent moved to a higher-rent district and amassed 5,123 performances before winding up as the seventh longest-running book musical in history.

And this was at the Nederlander Theatre, yet – a playhouse that was infamous for having flop after flop, making it the one venue that Broadway producers were least likely to book. Want proof? Take the 68 shows that played at this house during the previous 42 years, add all of the number of performance they played -- and combined they STILL don’t equal Rent’s total.

The original cast of Rent at the Nederlander Theatre (Photo by Joan Marcus)

Now that we’re living in America at the start of the millennium, we’re approaching 10 million, five hundred twelve thousand minutes since Rent began its march on musical theater history – and, sad to say, the same amount of time since Jonathan Larson unexpectedly died on Jan. 25, 1996 from an aortic aneurysm. It happened when his friends and relatives were planning to celebrate his upcoming 36th birthday on Feb. 4.

In a musical Larson had written years earlier, he expressed the angst of turning 30. Everyone who’s ever approached that age has felt similar anxiety, but sadly enough, Larson turned out to have a point. Little did he know that when The Big Three-Oh arrived that his life was actually 5/6ths over. What’s worse is that he died before Rent’s first public performance, so he never knew that his work would soon be a runaway success that would also win the Best Musical Tony and the Pulitzer Prize.

Today, Larson would be on the cusp of turning 56. What musicals we’ve been denied! He had an extraordinary gift for melody; few rock scores for musicals have ever been as intoxicatingly hummable. What a skillful way he had of defining his characters, too. In “Tango: Maureen,” the well-brought-up Joanne says that she learned how to dance “with the French ambassador’s daughter in her dorm room at Miss Porter’s” while suburban-reared Mark admits his instruction came from “Nanette Himmelfarb, the rabbi’s daughter at the Scarsdale Jewish Community Center.” Despite the disparity in their backgrounds, they both can do the dance, can’t they?

Yes, although it’s been said many times, many ways, musical theater lost a great deal when Larson died. Putting it another way: Stephen Sondheim wouldn’t have been able to give us Company, Follies and many other musicals had he died before his 36th birthday.

I vividly remember an incident in the early ‘90s, right around the time that Larson was turning 30. I had planned to attend an ASCAP Workshop, but arrived late and found a maelstrom in progress. The panel was sharply divided on the worth of selections that Larson had just presented, and so was the audience. There had to have been at least 20 minutes’ worth of yelling and screaming -- I do not exaggerate – in which some thought Larson’s work brilliant and others found it worthless. Meanwhile, I was wondering what I’d missed. How would I have felt if I’d heard the songs? With which faction would have I agreed? I’ve been late to precious few theatrical events in my time, but, oh, how I’ve often regretted my tardiness on this occasion.

Were the selections that night from Rent? They could have been, for Larson had begun work on it in 1988. Actually, writer Billy Aronson first had the inspiration to update La bohème and center on the Upper West Side’s many struggling and starving artists. Larson, however, thought the residents of Alphabet City would make more colorful characters.

Jesse L. Martin, Anthony Rapp and Taye Diggs in Rent at the Nederlander Theatre (Photo by Joan Marcus)

So Puccini’s seamstress Mimi, suffering from tuberculosis, became an erotic dancer with AIDS. She’d be the only one to retain her first name from the Illica-Giacosa libretto: Rodolpho the poet became songwriter Roger; painter Marcello morphed into videographer Mark; singer Musetta became performance artist Maureen; philosopher Colline became Collins, an NYU philosophy professor who would now become romantically linked with transgender percussionist Angel Schunard, who almost kept his Bohème name; he had been Schaunard, a musician before Larson rechristened him. The biggest change came via counselor Alcindoro, who became Joanne, a lawyer and Maureen’s new lover.

Aronson later dropped out (which must still haunt him), but Larson continued to write the book, music and lyrics. In addition to AIDS, they dealt with drug addition, transvestism, homosexuality, civil disobedience and vandalism. Such subjects brought it enough notoriety to entice an entirely new generation to enter a Broadway theater – and/or sleep outside it while waiting to get tickets. Bless the producers for initialing those $20 front-row seats so that young theatergoers could be treated as first-class citizens and not last-row-balcony occupants. “Rentheads,” they were called. Had any musical ever had so many groupies that they required a name?

Many of them attended a Rent panel discussion I moderated in 2002 at the now-late-and-lamented Musical Theatre Works. Director Michael Greif, musical director Tim Weil and star Anthony Rapp were on hand to tell about the evolution of the landmark musical. A few minutes after the discussion began, in came a young woman who approached us. “Are you Daphne Rubin-Vega?” I asked. After she nodded, I said “I didn’t recognize you without the handcuffs” – quoting one of Roger’s more piquant lines.

Alas, how much happier we all would have been had Larson been on hand to partake. Rubin-Vega recalled the wonderful “peasant feast” he used to annually hold for his friends. But at the 1995 one – the final one, not that anybody knew that then -- only the Rent cast was invited -- “because,” she said, “we were now his new family.”

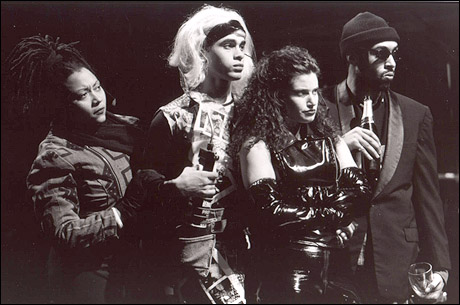

Fredi Walker, Wilson Jermaine Heredia, Idina Menzel and Jesse L. Martin in the original production of Rent at the Nederlander Theatre (Photo by Joan Marcus)

In those six years after Rent’s opening, many cynics had alleged that the show had reached its smash-hit status partly because of Larson’s unexpected death and the media circus that had ensued. “That’s why they call them cynics,” snapped Weil. Rapp said he was still smarting from the London critic who’d said that Larson’s dying was “a good career move.” The Rentheads and most everyone else winced, hissed and booed when they heard what the boor had written.

“I’d done Rent workshops dating back to 1994,” Rapp said, “and I can tell you that many times after we’d performed, people came up afterwards and swarmed all around Jonathan. That doesn’t often happen with authors, but it sure did in his case. Nobody knew then he was going to die. So if he had lived, he would have had great success and even more people all around him.”

Even by the second time I saw Rent in 1997, Mimi’s “AZT break” seemed futile, for this drug was no longer considered of much consequence in fighting AIDS; thus, seeing Mimi and Roger pin their hopes on it was sad. When I brought this up, Greif said he had never considered updating the show. If it was suddenly a period piece, so be it. That’s why he’d recently admonished new cast members who’d incorporated dance moves that hadn’t yet been invented in the long-ago ‘90s.

(Proof that Greif always wanted to keep Rent as is was given in 2011, when he directed the off-Broadway revival. Aside from set and costumes changes, it was Rent as usual. If Greif had updated, he certainly would have changed Collins’ line “My students would rather watch TV” to “My students would rather surf the ‘net.”)

At the 2002 discussion, I wondered if the cast members had been well-versed in La Bohème before they began work on the show; none was. But, I asked, did most of the people know anything about Broadway? Greif mentioned that he wanted to try casting kids who didn’t necessarily have much theater experience. As for the oft-made complaint that Rent’s going to Broadway was a selling-out akin to Mark’s selling his incriminating videotapes to a TV magazine show, Greif denied it. “Jonathan was clearly a Broadway baby,” he said, “and would have welcomed the chance.” As for Rapp, he frankly admitted that he was thrilled to get back to Broadway, for before Rent, he was -- yes! -- toiling in Starbucks.

After I asked if cast members lost music that they regretted parting company with, Weil mentioned a song about a door and a wall that Rubin-Vega much admired, too, although Rapp seemed astonished to hear that both had liked it. Rapp also recalled a lyric that went something like, “Mr. Negative, you’re HIV-positive.”

The most poignant moment occurred when an audience member asked the panelists if they’d had much support from their parents when they were starting out in theater. Rapp mentioned that his mother had helped start his career when he was nine after she’d seen him shine in some Pennsylvania summer camp productions. Sad to say, during the genesis of Rent, she discovered that she was dying and managed to see the show only once, albeit on that most exciting opening night. “Because she was sitting in the first row of the mezzanine,” Rapp said, “I got to see how happy she was all performance long.” (He would later write a book on this period of his life called Without You: A Memoir of Love, Loss and the Musical Rent.)

Yes, once again, the joy of Rent had been tempered by death - but Larson’s message of “It’s not how long you’re here, but what you do while you’re here” continues to live. In fact, many actors who perform Rent today weren’t yet born when the show began its original run. Indeed, how many Rentheads met while waiting in line for tickets, fell in love, married and had kids of their own who are now perilously close in age to the characters depicted in Rent? And do these children of Rentheads already think of their mothers as “The Wicked Witch of the West” or their parents as intrusive as Joanne’s?

(You bet. Some things will never change.)

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com, Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.